Reviewed by Phil Novack-Gottshall (Benedictine University, Lisle, IL)

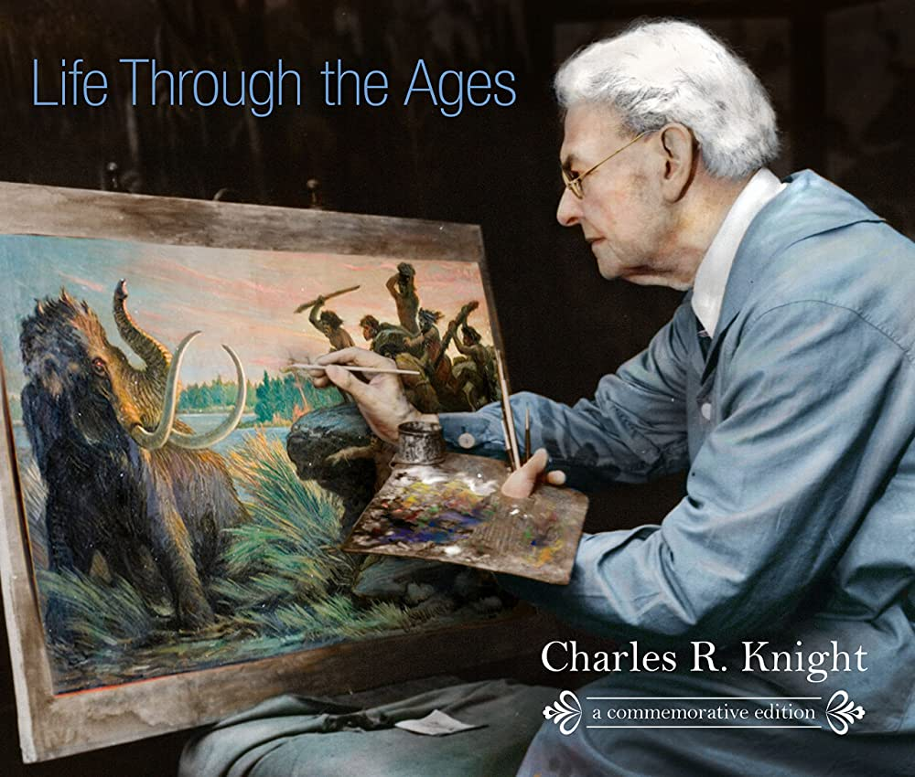

Knight, C. R. 2017. Life Through the Ages: A Commemorative Edition. Forewords by S. J. Gould and Introduction by P. J. Currie. Indiana University Press, Bloomington, IN.

Visual depictions of nature offer powerful tools to shape perceptions about the world around us and the myriad organisms that inhabit it. These images can even motivate students to pursue science and to give shape to scientific ideas and professional values. My own choice to study biology and fossils owes at least some debt to the monthly free screenings of Audubon Society documentaries my parents brought us to at a local high school. Later, when we visited Philadelphia’s Academy of Natural Sciences, and later the Smithsonian’s NMNH, I spent countless hours in rapture of the many dioramas capturing wildlife in all its glory. As a college intern in both museums, my fondest parts of each day involved walking through the exhibits on my way in and out from my shift. My two most-favorite movie scenes are the lumbering dinosaurs in Disney’s Fantasia (set to my still-favorite work of music, Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring) and the awesome scene in Jurassic Park when we first see the dinosaurs promenading on the grassland. And my favorite paleontological text is Stuart McKerrow’s (1982) Ecology of Fossils, economically depicting snapshots through geological time of live, dead, and fossilized taxa (followed closely by Steve Stanley’s 1970 memoir illustrating radiographs of living bivalves in situ). The commonality of these influences is a scientifically-informed artist bringing ancient ecosystems back to life. So it’s little surprise I became a paleoecologist who, in most of my research, is motivated by understanding how ancient animals walked, fed, reproduced, and simply inhabited their own world.

Looming largest among the artists who brought these worlds to life ranks Charles R. Knight. Originally published by Knopf in 1946, Indiana University recently republished Knight’s Life Through the Ages, a series of 33 black-and-white sketches Knight drew depicting life since the Cambrian. Most include accompanying short texts to guide the reader on how they fit into the entirety of evolutionary history. The 2001 hardcover re-issue featured a new forward Stephen Jay Gould and an introduction by Philip Currie. This 2017 version republishes this work in its entirety, but now in paperback.

The drawings include the standard images of evolutionary history, in large part because Knight was the one to make them iconic. Passing rapidly through the Paleozoic in (only!) five scenes, we begin with Cambrian invertebrates in the Burgess Shale before moving on to Devonian fishes, a Carboniferous coal forest with the amphibian Eryops, and two Permian scenes (Dimetrodon and the Karoo Basin). The Cambrian scene is presumably an alternate version of the colored version Gould used as the cover for his Wonderful Life. Not surprisingly, Knight includes four scenes depicting dinosaurs, plus a scene of flying “reptiles” (Archaeopteryx and a pterodactyl, both with wings outstretched along the same cycad frond, either about to begin battle or doing a weird dance-off) and a marine scene with mosasaurs. Sadly, not a single post-Devonian invertebrate is to be found in the book. Plants fare better, albeit to round out the habitat. Typical representatives of Paleozoic seedless plants, Mesozoic gymnosperms, and Cenozoic angiosperms play bit parts in the scenery. Most of the book focuses on Cenozoic mammals (elephants and mammoths, dogs and cats, horses and other herbivorous quadrupeds, sloths, wolves, and primates), but not before a litany of birds (auk, eagle, loon, and Hesperonis), sharks, whales, and extant reptiles. Several of the images are presumably earlier studies or reprints of drawings commissioned by other museums or zoos (such as the American Museum of Natural History, Natural History Museum of LA County, Field Museum, Bronx Zoo, and Lincoln Park Zoo).

It is an amazing fact that Knight was legally blind, having suffered a childhood eye injury and terrible astigmatism. Yet, the drawings demonstrate Knight’s deep knowledge of comparative anatomy (especially for vertebrates), and much time spent closely observing animals (often in the New York Zoological Park and Chicago’s Lincoln Park Zoo). His drawings of extant animals tend to be more precise and realistic—cleaner lines and shadings, more natural poses—than extinct ones. For example, the two elephants are so detailed you can almost make out each scraggly hair, and comparatively make the prior image of the mammoth look like a rush job, with more time spent on the tusks than the rest of the body. (And the wretched humans—in both the image with the mammoth and the sad ones defending their turf from a fearsome cave bear—are among the worst in the book. Knight clearly relished drawing animals more than humans.)

In all his drawings, Knight renders each animal as a vital and living presence, with autonomy and a self-determination to carry on whatever behaviors it required to survive. My favorites include the startling tiger looking straight at you, with an expression in its wrinkled nostril where it’s hard to imagine who was more terrified while walking through the jungle, although there’s little doubt who’d have walked away. (The image would make a perfect tattoo.) I also love that Knight included an axolotl, or perhaps a larval amphibian, in his Carboniferous scene with smug Eryops, as if to imply that ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny. And his spectacular drawings of modern reptiles (iguana, Galapagos tortoise, crocodile, rattlesnake, and a Komodo monitor soon after its first arrival in the NY Zoological Park) are better than any photograph I’ve ever seen of them.

Knight’s accompanying text is charming, written in the slightly ever-so-staid language well suited to mid-Century American pedagogues (and sometimes cringe-worthy to modern audiences). In his own foreword, he claims his motivation was to not only show life through the ages, but to also include their “modern representatives, in an effort to bridge the gap between the past and present.” He also presents a concise history of evolutionary biology, citing Cuvier’s catastrophism, Lamarck’s transmutationism, and Darwin’s natural selection. Most essays describe the life of each focal animal—how it fed, moved, and so on—but the subtext always conjures how the animals were well adapted for their individual habitat, their interactions with other species, or their connection to their broader evolutionary heritage. If I had read this as a child, my imagination would have been transported in time along with each scene.

Gould’s preface, among his most restrained writings, gently diatribes against the Scala Naturae and the assumption of evolutionary progress in the history of life. Although Knight’s choice of animals clearly follows this order, my sense is that Gould held back his typical jeremiad because of his immense respect for Knight’s powerful impact, both on Gould himself as a child and on the broader science of evolutionary biology. Gould writes that Knight “more than any other person, revivified the dry bones and placed them, as animals, within the pageant of vitality.” Philip Currie’s introduction focuses on the revolutionary re-interpretations of dinosaurs since Knight wrote his book, discussing the latest (pre-2001) insights on their posture, behavior, ecology, and evolutionary relationships, luckily able to fit in the then-new discoveries of feathered dinosaurs from China. But like Gould, Curie emphasizes more the power of Knight’s images and their scientific accuracy of their time.

Sure, there are some errors, given hindsight. But science, and paleontology especially, has changed much since the first edition was published, and I won’t dwell on them here. Knight portrayed the science better than most. The most vivid errors involve the pre-Dinosaur Renaissance perspective of dinosaurs (and their allies) as “strange,” “slow-moving dunces,” “too big and too ungainly for their own good,” and “the stupidest member of a very moronic family,” “no more sinister beings [having] ever walked the surface of this earth.” Yet, his Mesozoic drawings do not portray these characteristics. They revel, instead, in their awesomeness, their dominance of the land (and sea and air for their compatriots), and even their beauty. His description of Allosaurus—as essentially “a plucked turkey with a long tail and little front legs with claws instead of wings, conveys a pretty good idea of what all these flesh-eating reptiles looked like” —is more accurate than most contemporary descriptions. Sure, ignore the tail dragging and the semi-aquatic sauropods. There’s a reason, more than historical convenience, that the Field Museum still displays Knight’s fantastic 1926–1930 murals in their hall of dinosaurs, among elsewhere in the exhibits.

Speaking of the Field, Knight’s drawing of Bushman, the first and most famous American gorilla in captivity, is also magnificent, hardly fitting in the margins of the page, as if to emphasize his majesty. When Bushman died in 1951, after 21 years of worldwide fame in captivity in the Lincoln Park Zoo, his remains were transferred to the Field Museum, where he was taxidermied by Frank Wonder and Leon Walters and today remains on commanding display in the ground-level east entrance, in the identical posture drawn by Knight when observed living in captivity. Using their local connections and trading leverage, my own Benedictine University’s founding biology monks wound up obtaining the post-cranial skeleton of Bushman, which now rests on display in our own Jurica-Suchy Nature Museum collection, 20 miles west of Chicago.

Charles Knight’s Life Through the Ages is a wonderful book, and kudos go to Indiana University Press (and their paleontological editor James Farlow) for continuing to make this visual treasure available to a new generation. Sadly, since this book was reviewed, it seems to have become no longer available. Search your used book repositories to discover an available volume instead.