Reviewed by Paul Strother (Boston College Weston Observatory)

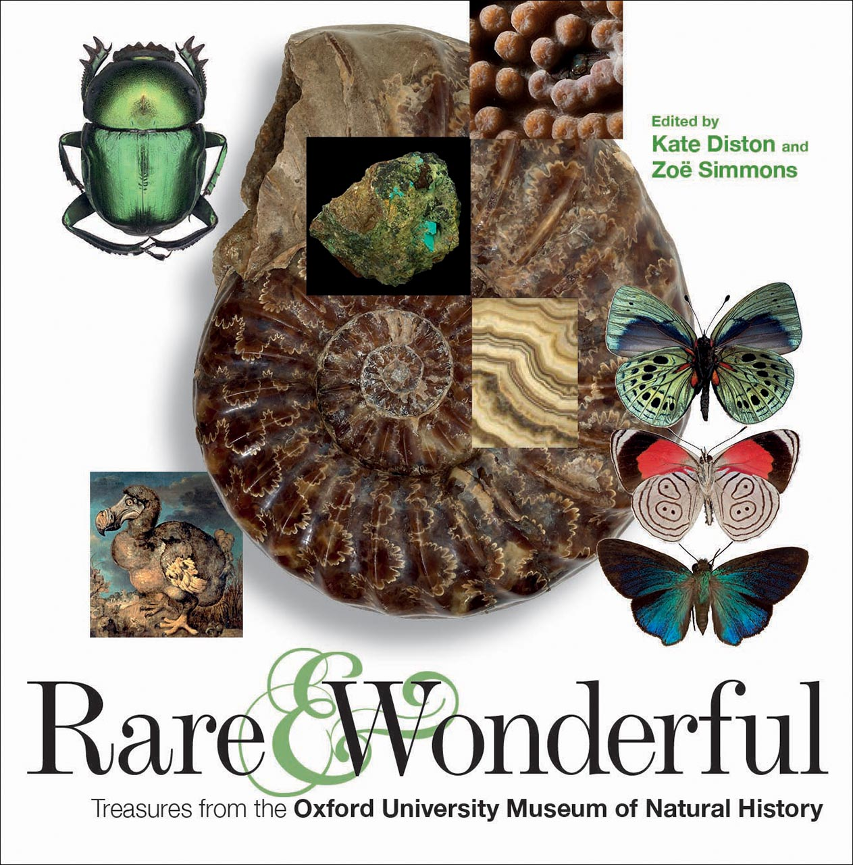

Diston, K. and Z. Simmons, eds. 2019. Rare and Wonderful: Treasures from Oxford University Museum of Natural History. Bodleian Library, University of Oxford, Museum of Natural History, and University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL. 224 pp. ($21.00 cloth with 40% PS discount.)

This book is a beautifully illustrated overview, or perhaps, snapshot, of the various interesting historically and scientifically valuable “objects” housed in the Oxford University Museum of Natural History. Each set of illustrated objects is accompanied by one or two pages of descriptive and relevant anecdotal text. The Museum, which was completed in 1860, inherited the European tradition of cabinets of curiosities that was prevalent prior to the invention of words like biology and geology. One gets a very good sense of this pre-science world of gentlemen collectors and early purveyors of Natural History, documenting not just the plants and animals of the world, but the entire gamut of objects that can be found in the natural world. This list of curiosities begins with the remains of the extinct Dodo, followed by many interesting fossils: The giant Irish Elk (which, we are informed, is not an elk), the skull of Stratesaurus (an early and relatively small plesiosaur), and the finest fossil fish ever (according to Louis Agassiz in 1835). A 25 g piece of Mars can be had in the Nakhla meteorite which fell in Egypt in 1911. You also find 1.7 kg of the Siberian Kransojarsk meteorite, which is historically interesting as the first meteorite to be described as an extraterrestrial object. Lyell’s fossil collection is available for study and it’s on-line here. There are numerous tidbits about the design of the building: John Ruskin and the Pre-Raphaelites were involved. A fine photograph of Charles Darwin at 58 apparently was his favorite.

So, other than a true miscellany of interesting annotated illustrations of stuff in the museum, what is this book supposed to be and who is it for, really? Perhaps it’s a coffee-table book, although a small one. It is not really a guide to the museum, although after reading it one might be more inclined to want to visit the place. I would say for certain that reading before going would certainly generate an enhanced appreciation of a visit to the Oxford University Museum of Natural History. One does not usually gain a full appreciation of a building with such a history just by attending a reception. (I remember some well-worn stone stairs). Perhaps, if you teach Paleontology, you will find a few worthwhile historical tidbits to be included in a lecture here and there. I was reminded of the story of the “lying stones” of the early 18th century, fabricated “fossils” used as a hoax to discredit Dr Johann Beringer in Würtzburg. Apparently some 2000 of these were made, two of which made their way to Oxford via William Buckland in 1835. (Tyler’s Museum in Haarlem, The Netherlands, which open in 1784, has a dozen or so on display.)